The night sky is so much more than pretty lights in the heavens. They’re whole worlds, and lots of them not at all like Earth. Scientists have spent decades mapping these far-off planets, and what they’ve found out has made us completely rethink our place in the universe. From gas giants bigger than Jupiter to rocky worlds where life may exist, the story of planet mapping is one of science’s most churning, dynamic adventures.

How Do Scientists Get the Solar System Model to Look So Accurate?

You may wonder how in the world you even make a map of a planet that’s so far away we can barely see it as a dot through our most powerful telescopes. The solution is thanks to some pretty nifty ideas scientists have come up with over the years.

The Transit Method: Watching Shadows

A particularly fruitful way to find and map planets is the transit method. Think about holding a baseball up in front of a streetlight. And when the ball blocks it, then that light dims, right? That is what occurs when a planet transits, or passes in front of its star. Researchers calculate how much the star’s light dims and use that to determine the planet’s size. If the planet obstructs just 1 percent of a host star’s light, it is likely about the size of Jupiter. If it only obscures 0.01 percent, it is probably closer to Earth’s size.

Radial Velocity: The Wobble Dance

Here’s a neat thing: when a planet goes around a star, the star doesn’t stay put. In fact, it wobbles a little bit due to the planet’s gravity. This wobble is something that scientists can measure by gazing at the light of the star. As the star moves toward us, its light tilts a bit toward blue. If it’s moving away, it moves to the red. This wobble is what tells us how massive the planet is and how far it orbits its star.

Direct Imaging: Taking Actual Pictures

Sometimes, with very good telescopes, scientists can even photograph far away planets. This is super hard because stars are millions of times brighter than planets. It’s trying to see a firefly by the lighthouse. But by suppressing the light of the star using specialized instruments called coronagraphs, astronomers have been able to photograph a few planets directly.

The Astounding Variety of Worlds Out There

Back before we began seriously charting distant planets in the 1990s, most scientists also believed that other solar systems would closely resemble our own. Boy, were they wrong! The universe was a lot more creative than anyone ever thought.

Hot Jupiters: Blazing Gas Giants

One of the very first kinds of exoplanets we found stumped astronomers completely. These planets are giant, gaseous worlds, like Jupiter; they just happen to orbit super closely to their stars — closer, even, than Mercury is to our Sun (imagine if Earth orbited an oven and you get the idea). Temperatures on these “Hot Jupiters” can soar past 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s plenty hot enough to liquefy iron!

Hot Jupiters like HD 189733 b are a type of planet that was among the first exoplanets discovered. The glass may rain sideways, they found, because of the intensive winds that blow across its surface. The entire planet is blue, but not for the reason you might think — it’s silicate particles in the atmosphere that are actually scattering blue light.

Super-Earths: The In-Between Worlds

Larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune, Super-Earths are all over the Milky Way. Our solar system has none, but actually they are the most common type of planet in our galaxy. The researchers say about 30 percent of all stars have at least one super-Earth in orbit.

They’re interesting because they might be rocky like the Earth, or they may be mini-Neptunes with thick hydrogen atmosphere. There is one super-Earth, named LHS 1140 b, located squarely in the habitable zone of its star, where liquid water could pool. It is about 1.7 times the size of Earth and has attracted scientists looking for life.

Ice Giants and Water Worlds

Some distant planets seem to be completely covered in water — not like the oceans that we have here, but super-heated water at high pressure. These “water worlds” could harbor oceans hundreds of miles deep. Among the candidates is K2-18 b, a planet located approximately 124 light years from Earth. Scientists have detected signs of water vapor in its atmosphere, and the exoplanet is one of most promising places to search for life beyond our solar system.

| Type | Size (In Earths) | Similarity to Earth | Features | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Jupiters | 10-15 | Larger | Extremely hot, very close to star | HD 189733 b |

| Super-Earths | 1.5-2.5 | Larger | Rocky or gaseous, diverse atmospheres | LHS 1140 b |

| Mini-Neptunes | 2-4 | Smaller | Thick hydrogen/helium atmospheres | K2-18 b |

| “Earth-like” Rocky Planets | 0.8-1.2 | Similar | Solid surface, potentially habitable | Proxima Centauri b |

What Planet Atmospheres Tell Us

It’s not just knowing the size and whereabouts of a planet that you’re mapping. The atmosphere itself is what’s interesting, and we can learn about that because we have this shining white light source peeking through it.

Reading the Chemical Fingerprints

Each element and molecule absorbs light in its own characteristic manner. When starlight filters through an exoplanet’s atmosphere during a transit, some colors of light are absorbed. When we split that light up into a rainbow and let it spread out across the sky (that’s called a spectrum in science), then we can see which chemicals are there. It’s as if you are being able to take a fingerprint of the planet.

They found strong evidence for water vapor on the planet WASP-96 b. On others, they’ve turned up sodium, potassium, and even molecules — carbon monoxide and methane. Every discovery contributes to our understanding of what these alien worlds are actually like.

The Hunt for Biosignatures

This is where it gets good. Scientists are specifically searching for mixes of gases that could be a signpost of life. Here on Earth, most of the oxygen in our atmosphere comes courtesy of plants and algae. If we were to find a planet that had lots of oxygen and methane together, it would be really hard to explain that abiotically.

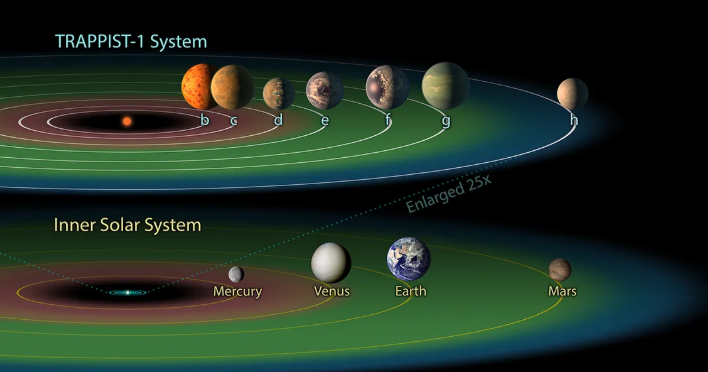

One of the planets, called TRAPPIST-1e, in particular has scientists excited. It is rocky, roughly the size of Earth, and resides in its star’s habitable zone. Planets like this are exactly what future telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope will be looking to find in the search for biosignatures in their atmospheres.

Mapping Techniques That Changed Everything

The technology for mapping faraway planets has improved exponentially only in the past 10 years.

Space Telescopes: Above the Noise

Earth’s atmosphere: ideal for breathing, but lousy for astronomy. It obscures our view and prevents some kinds of light from reaching the ground. That’s why space telescopes, such as Kepler and TESS — and the James Webb Space Telescope when it gets into action — have been game changers.

The Kepler Space Telescope, active from 2009 to 2018, detected more than 2,700 known exoplanets. It gazed at a single patch of sky, which held about 150,000 stars and waited for little blips of dimming that would signal planets had passed in front. Now, the TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) is following up this work by scanning the sky to map out planets around our closest stellar neighbors.

Spectroscopy: The Light Detective Work

Today’s spectroscopy can take light apart in such exquisite detail that scientists record extremely subtle variances. In 2021 the James Webb Space Telescope, with infrared vision that allows its glass-eyes to see through clouds in planet atmospheres and glimpse molecules previously invisible, was launched.

In 2023, Webb spotted carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of a gas giant known as WASP-39 b. That may not sound thrilling, but it was the first time we’d ever clearly detected this molecule on a planet outside our solar system. It demonstrated that our instruments are now finally good enough to really do proper atmospheric chemistry on other worlds.

The Most Mind-Blowing Discoveries

Some of what we have discovered when mapping distant planets sounds more like science fiction than it does science fact.

Planets Orbiting Multiple Suns

You know, Tatooine in Star Wars, which has two suns? Well, it turns out that’s not just movie magic. A number of planets have been found orbiting binary star systems — systems that contain two stars, each in orbit around the other. One planet, known as Kepler-16 b goes around two stars and if you were standing on its surface, you would see not one sunrise or sunset but two each day.

Rogue Planets: Planets Without a Star

Not all planets orbit stars. Some have been kicked out of their star systems and now drift in solitude through space. These “rogue planets” are extremely hard to find, in part because they lack the light of a star to guide us toward them. Scientists believe there could be billions of such lonely worlds drifting across our galaxy.

Lava Planets: Literal Hell Worlds

Some planets trace such close orbits to their stars that they have surfaces of molten rock. That’s now one of those worlds, 55 Cancri e. They have surface temperatures that are approximately 4,400 degrees Fahrenheit: hot enough to make the “ground” an ocean of lava. Astronomers have been able to map its temperature variation across its surface and found that one side is much hotter than the other due to it being tidally locked (one face always points at the star, like our Moon does with us).

Planets That Are Older Than They Should Be

Among the strangest finds are planets that formed much earlier than scientists had believed was possible. The fact that the planet discovered is about 12.7 billion years old means it is nearly as old as the universe itself, which at 13.8 billion years old has made many of its stars to planets an intriguing concept, a theory and a reality when it comes to exoplanets. It congealed when the universe was still a baby, long before there were anywhere near as many heavy elements floating around to form planets. Its presence is challenging scientists to rewrite their theories of how planets come to be.

What This Means for the Search for Life

The point of mapping far-off planets is not just to document them, but to find out if we are alone in the universe.

The Habitable Zone: The Goldilocks Region

Researchers pay a lot of attention to planets in the “habitable zone” — the orbit around a star where temperatures are just right for liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface. Not too hot, not too cold, but just right, as in the story of “Goldilocks.”

Yet now we find that the habitable zone is more complex than we once believed. Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons is also not located in the habitable zone of sun but it hosts a probably subsurface liquid ocean under its icy shell which is heated by gravitational pressure from Jupiter. That life may reside where we had not previously considered it.

The “Just Right” Planet Checklist

After making maps of thousands of planets, scientists have refined their search for what they hope could be signs of life on potentially habitable worlds:

- Rocky surface – On the sunny side of an exoplanet, this stability is provided by land

- Liquid water – ALL life on Earth requires water

- Stable orbit – Wild swings in temperature would make life difficult

- Protective atmosphere – To protect against radiation

- The presence of the magnetic field – By deflecting dangerous particles from the star

- Just the right size star — not too big (burns too hot and dies too fast) or too small (requires planets to orbit close, getting blasted with radiation)

Statistical Hope: The Drake Equation Gets Real Numbers

For years, researchers have made use of the so-called Drake Equation — a method to generate an estimate of how many intelligent civilizations might live in our galaxy. But almost all of the numbers in the equation were total guesses. Now, with mapping of the planets, there’s real data for several variables.

We now know that:

- Most stars have planets

- Some 20-50% of Sun-like stars have one or more planets in the habitable zone

- Rocky planets are extremely common

- Ingredients for life (water, organics) are widespread across the universe

These numbers are tantalizing, and if it’s easy for life to emerge under the right conditions, there might be millions or even billions of habitable planets in our galaxy alone.

Technology Pushing the Boundaries

The future of planet mapping appears brighter still than its historical glow.

Next-Generation Telescopes

Several game-changing telescopes are already in operation or on their way:

The James Webb Space Telescope is already revolutionizing exoplanet science with its ability to analyze atmospheres at unparalleled detail. The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which is due to launch in the mid-2020s, will hunt for planets using gravitational microlensing — the act of a star’s gravity magnifying a planet, even one that may be far away from its star.

Telescopes on the ground are also being upgraded. And the Extremely Large Telescope in Chile, when it is finished, will feature a 39-meter mirror — roughly half the length of a football field. The telescope will also be able to directly image Earth-sized planets orbiting nearby stars and study their atmospheres.

Artificial Intelligence: The Learning Never Stops

Modern planet mapping creates gobs of data — so much so that humans could never analyze it all with their human brains in a human lifetime. This is where artificial intelligence steps in.

Using machine learning algorithms, these systems can sift through millions of light curves (graphs showing how the brightness of a star changes over time) and identify the subtle fluctuations in those curves that indicate a planet passing between us and its host star. AI has already discovered planets that human astronomers never saw. In 2017, scientists working with a neural network trained on Kepler data found two planets that had been lurking in the data for years.

Challenges Scientists Still Face

For all that progress, mapping far-off planets is still astoundingly hard.

The Distance Problem

Even our nearest stellar neighbors are mind-bogglingly distant. Proxima Centauri, the closest star system, is 4.2 light-years away. In other words, light would travel 4.2 years to get from there to here. Even our speediest spacecraft would need some 80,000 years to get us there.

This separation renders the close-up observation nearly impossible. Although we’ve discovered a planet around Proxima Centauri (dubbed Proxima Centauri b), we know little about it. We know its approximate size and orbit, but we still don’t know for certain whether it has an atmosphere or what the surface looks like.

Atmospheric Interference

Many of the most intriguing molecules we hope to detect in the atmosphere of planets — such as oxygen or phosphine, whose recent detection by other researchers around Venus has been much discussed — absorb light at the same wavelengths that terrestrial molecules do, too. It’s as though you’re trying to make out a whisper at a rock concert. On the ground, scientists must employ clever mathematical techniques to subtract out Earth’s atmospheric signals — which in turn introduces some uncertainty into the measurements.

Small Signals, Big Noise

The signals scientists deal with are exceedingly tiny. When an Earth-size planet transits its Sun-like host star, it blocks just about 0.01% of this light. That’s a bit like trying to measure the increased brightness from a car’s headlights when a fruit fly flies in front of them. Other sources of such variation — like starspots or instrument noise — can easily drown out the signal.

How This Changes Human Perspective

What scientists take away from mapping distant worlds isn’t only scientific — it’s philosophical.

Earth Just Happens to Be Habitable (That May Be Rare)

For much of human history, we believed that the Earth was at the center of everything. Then we discovered that we orbit the Sun. Then we discovered that the Sun is merely one of hundreds of billions of stars in our galaxy. Now we know that planets are everywhere — our solar system is not special or even unique when it comes to having planets.

But this is the kicker: The more planets we map, the more we understand how perfectly suited Earth is for life. We have discovered a lot of planets, but we haven’t found Earth 2.0 yet. The unique combination of Earth’s size, its moon, distance from the Sun, protective magnetic field, plate tectonics that recycle chemicals — all of these make our planet pretty cool after all.

The Overview Effect

Astronauts frequently mention the “overview effect” — the changed perspective that comes from seeing Earth from space. Mapping planets in the far reaches has a similar effect. When you start to think that there are probably billions of habitable planets in the galaxy, that makes little human squabbles and differences take on a new perspective. We’re all on this one planet together, a small fraction in an unimaginably huge universe.

Motivation for Environmental Protection

An unexpected dividend of mapping other planets is how it has altered our appreciation for Earth. We know now just how rare and precious are the conditions underpinning life. Venus is a runaway greenhouse with temperatures so hot it could melt lead. Mars then lost most of its atmosphere and turned into a frozen desert. Earth could just have easily turned out like one those planets, but it didn’t. This knowledge makes it seem all the more urgent that we protect our natural world.

The Economic and Social Impact

Mapping the planet isn’t just about satisfying our curiosity — it has real-world impact.

Inspiring the Next Generation

New planet discoveries are headline makers and thinking stimulators for everyone, especially young people. Today, many scientists pursued their careers because they were inspired by the discoveries of humanity’s place in the universe. The constant stream of enthusiastic discoveries from planet mappers keeps the public interested in science.

Technology Spinoffs

The ultra-sensitive cameras and elaborate algorithms, not to mention the data processing methods used for planet mapping, are likely going to get used elsewhere. Astronomy technology has even been applied to medical imaging, quality control in manufacturing and smartphone cameras.

International Cooperation

It’s a planet-mapping effort that unites scientists from around the world. Information from telescopes such as Kepler and TESS is available freely for any researcher who wants to use it. Researchers in various countries co-author papers, trade observing time on telescopes and band together to solve challenges. In a world that often feels divided, this kind of collaboration has value all its own.

Where We Go From Here

The next century seems rich in more thrilling revelations.

The Search for Atmospheric Biosignatures

The James Webb Space Telescope, as well as future observatories, will devote much attention to probing the atmospheres of rocky planets in habitable zones. If we can find combinations of gases that would indicate biological activity — oxygen and methane together, say, or phosphine, or even industrial pollution — it would be one of the greatest discoveries in human history.

Direct Imaging of Earth-Like Worlds

Several mission concepts are being developed by scientists to directly photograph Earth-like planets orbiting other stars near the sun. One concept is for a colossal, space-based “starshade” — essentially a spacecraft that would fly alongside a telescope and block the light from the star, so you could see only its planet. Another idea involves ultra-sophisticated coronagraphs in the telescope.

These missions would not just take pictures — they would capture spectra that could yield information about surface features. Scientists could potentially find out if a planet has oceans, continents, and clouds — or even vegetation (plant life on the Earth reflects light in a certain way that’s known as the “red edge”).

How We’d Really Visit These Worlds

We may be a long way from any planets we might actually visit in our discoveries for signs of life elsewhere, but it is also light years away from any kind of human mission anywhere off-Earth that could support life. The Breakthrough Starshot project envisions sending minuscule space probes, powered by powerful lasers on Earth, to Proxima Centauri. The probes would be small and light enough that they could reach 20% of the speed of light, or get to Proxima Centauri in about 20 years, rather than 80,000.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many planets have we found out there?

As of 2025, astronomers have discovered more than 5,000 exoplanets (worlds outside our solar system) with thousands of others waiting to have their existence confirmed. NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope alone found some 2,700 planets during its mission.

Can we possibly see what these planets look like?

In most cases, we are unable to see other planets directly. We find them using indirect methods, by observing them as they move in front of their star or with the gravitational effects that they cause. But a handful of dozens of the large planets far from their stars have had actual images taken by advanced telescopes.

How long does it take to map out a planet?

It depends on the method. When searching for a planet with the transit method, you need to see at least 2-3 transits to be sure that it really is one (it might take months or years depending on the period of your planet). Constructing such a detailed atmospheric map could require years of repeated observations.

What is the nearest planet we have found that might be habitable?

Proxima Centauri b lies in the orbit neighboring our closest star, just 4.2 light-years from Earth. It is more or less Earth-size and it orbits in what may be the habitable zone, although we’re still studying its conditions. A handful of other prospects are nearby, including a few planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system, which lies some 40 light-years from us.

Might any of these planets actually foster aliens?

We simply don’t know yet. We’ve never found unequivocal evidence of life on any planet beyond our own. But with thousands of planets found around other stars and likely billions more in our galaxy alone, many scientists believe they may be at least probable for life. The issue is whether we will be able to notice it.

Why are scientists so interested in water on other planets?

Liquid water is a prerequisite for life as we know it on Earth. Water is a superb solvent (it dissolves many chemicals), it stays liquid over a wide range of temperatures, and it has nice properties useful for biochemistry. You could imagine life without water, and we do (life as we don’t know it does not require a blueprint).

The Bigger Picture: What It Means

Dozens of years spent mapping remote planets have taught us something deep: the universe is wilder, more varied, and more fabulous than we ever dreamt. We have found worlds that rain glass, planets orbiting two suns, planets older than they should be, and thousands of other examples that don’t quite fit into any of the categories we expected going in.

But maybe the most important lesson is that planets are all over the place. Virtually every star in our night sky plays host to planets. In our own galaxy, there are likely hundreds of billions of planets and tens of billions that could sustain life.

This knowledge changes everything. It is that the question is not “Are we alone?” but there are instead “How prevalent is life?” and “Who are our nearest neighbors?” The maps we are making now are equivalent to the first outlines in what will one day become detailed atlases of billions of worlds.

Each new mapped planet teaches us something new about how planets form, how they evolve and what conditions are necessary for life. Some lessons are ones we knew all along. Many surprise us completely. And every new finding helps illuminate our own planet, and our place in the cosmos.

The work continues. Fortunately, telescopes above and below the atmosphere already are collecting light from alien worlds. Computers are whirring, scanning this data for the telltale signs of new planets. Researchers are increasingly ambitious about their plans to study these worlds in greater depth.

We are living in a unique historical moment — the time when humans first discovered that worlds outside our solar system are, after all, out there and started to map them. We will look back on this period in the future, much the way we examine the Age of Exploration when people first drew maps of Earth’s continents. Only our maps do not encompass only one world, but possibly billions.

And the tale of creating maps for faraway planets is still being written. Who knows what in-depth discoveries the next decade will provide? What is certain is that the universe always has a way of surprising us, challenging our assumptions, and reminding us how much we still have to learn. Perhaps that’s what makes this journey so enthralling.