When Galileo Galilei aimed his telescope at Jupiter in 1610, he saw four bright spots moving around the big planet. These were not stars — these were moons, and they changed everything we thought we knew about our solar system. Now we know Jupiter has at least 79 moons and these objects are doing something amazing: they’re compelling scientists to re-evaluate nearly everything about how planets and their terrains accumulate and evolve.

These moons aren’t just cold, lifeless boulders careening through space. They are active worlds, with underground oceans, huge volcanoes and icy surfaces that break and grind in patterns not unlike the continents on Earth. As researchers study these far-off moons, they are finding that the general rules we thought governed planetary geography don’t always hold. What we are learning from the moons of Jupiter is rewriting textbooks, and it is opening our eyes to possibilities that we never saw — both here in our own solar system and on planets around other stars.

The Big Four: Galilean Moons of Jupiter

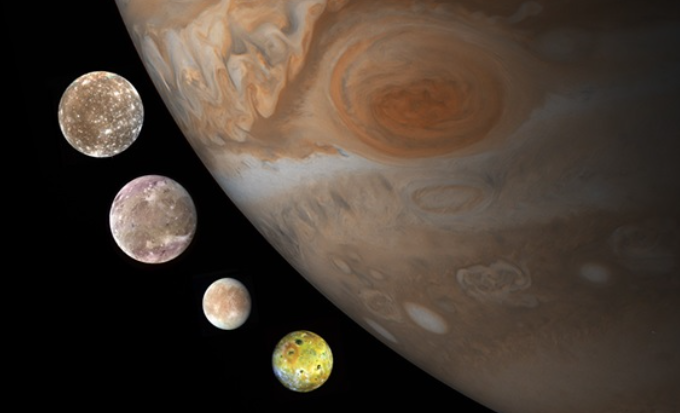

Jupiter’s four largest moons, named the Galilean moons in his honor, are Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. Each is different and collectively they make for a captivating laboratory in which to understand how the features of worlds come into being.

Io is the most volcanically active object in the entire solar system, with hundreds of volcanoes – some erupting lava fountains up to 250 miles high — painting its surface with bright red and yellow splotches. Europa harbors a big ocean under its icy shell, one that has more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined. With its own magnetic field, the moon Ganymede is the largest in the solar system, larger even than the planet Mercury. Callisto is the most cratered object we’ve laid our eyes on, and its terrain is shaped by tales that are billions of years old.

While these moons are special because of their individual traits, there’s something else intriguing about them. It’s that two of them are so near to each other and yet became such distinct worlds. The range defied traditional theories of planetary geography. Scientists expected similar objects forming in the same environment to look like kin, as siblings raised under the same roof. Jupiter’s moons, however, are more like completely unrelated strangers who simply share an address.

Tidal Heating: The Game-Changing Force

Before we began close study of Jupiter’s moons, scientists thought a world derived most of its internal heat from just two sources: left over heat from when the planet was formed in the first place and heat created by radioactive elements breaking down deep within it. This helped to explain why Earth has volcanoes and drifting continents, while our Moon is geologically inactive — three times bigger, the argument went, Earth kept more of its heat in storage and possessed more radioactive substance.

And then we found Io — everything changed.

Io shouldn’t be volcanically active. It’s about the size of Earth’s Moon, which fell geological silent for billions of years. But Io exhibits violent eruptions that burp material hundreds of miles into space. Some of its volcanic plumes are so strong that they generate transient atmospheres around the moon. The energy driving this activity is due to something known as tidal heating, and understanding it has literally revolutionized our understanding of planetary science.

What is Tidal Heating?

Imagine a rubber ball that you squeeze repeatedly in your hand. After a bit, that ball gets warm from all the flexing. That’s pretty much what is happening to Jupiter’s moons, only on a planet-size scale. Jupiter is so massive that it tugs on its moons, stretching them a little. But the moons are themselves all orbiting each other and so will pull on one another with their own gravitational forces, altering the strength and direction of these tides. That constant squeezing and stretching produces intense heat inside the moon’s bodies.

For Io, which orbits nearest Jupiter, this tidal heating is strong enough to liquefy rock inside the entire moon. Europa gets less heating but still enough to keep a liquid ocean warm beneath its ice. Further out, Ganymede and Callisto have gradually less tidal heating.

This find made scientists realize that planetary geography wasn’t a question solely of a world’s size or age. The gravitational setting is just as important, if not more so. A small moon in just the right spot can be more geologically dynamic than a much larger planet somewhere else.

Europa’s Ocean: Thinking Through What Makes a World Habitable

Prior to Europa, one of the primary places for searching for life in our solar system was Mars. The reasoning was simple: life requires liquid water, and rivers and lakes existed on Mars at one point in its history. But Europa changed that conversation once and for all.

Europa’s ice shell is a jumble of cracks, ridges and broken-up blocks called “chaos terrain,” and that is likely where slush or water might ooze through. By analyzing the motion and breaking of the ice, scientists concluded that a global ocean of liquid water lies beneath the icy shell. This ocean is believed to be 40 to 100 miles deep — much deeper than Earth’s oceans.

Implications for Geography Theories

Most traditional planetary geography theories revolved around changes that occur on the surface of a planet: Wind and water erosion, volcanic activity, asteroid impacts and movement of tectonic plates. They had assumed that the good geology was going on at the outer edge of worlds.

Europa’s internal ocean disintegrates this notion. The most critical geographic processes that occur on Europa take place in a location we can’t even glimpse directly. The ice shell over the ocean cracks and shifts as the water below circles. These warm spots in the ocean melt ice from below and create features on the surface. Salt, and other substances from the ocean, could be being brought upward through cracks, causing a discoloring of the ice as well as changes to its substance.

This realization has massive implications. If Europa’s secret ocean gives rise to complex surface geography, then perhaps the same is true on other icy worlds. In an instant, dozens of moons and dwarf planets that scientists had written off as geologically dull suddenly became captivating destinations to send a spaceship. Enceladus (one of Saturn’s moons), Titan (Saturn’s largest moon) and even far-off Pluto could all be homes to subterranean oceans which influence their surface characteristics.

Ganymede’s Magnetic Mystery

Ganymede is the only moon in our solar system that has its own magnetic field, a finding that surprised scientists more than 20 years ago when it was discovered by the Galileo spacecraft. Magnetic fields usually arise from liquid metal that is moving in the core of a planet — which is what generates Earth’s magnetic field. But Ganymede is an icy moon. What in the world could possibly be producing this magnetism?

It turns out that Ganymede has its own thermal-weather system in which its ice on one side sublimates, and then it migrates around to cold-trapped areas. Despite being further from Jupiter than Europa, Ganymede is heated to the point that it would be entirely liquid if its core were composed strictly of iron. This core, together with Ganymede’s rotation, leads to a magnetic field.

But the geography of Ganymede tells an even more compelling story. The surface has two varieties of terrain: dark, heavily cratered regions that are very old, and light grooved terrain much younger in age. The grooved terrain resembles the result if someone stretched out the moon and formed parallel ridges and valleys that extend hundreds of miles.

What Created the Grooves?

Like Europa, scientists think Ganymede had (and may still have) a subsurface ocean. Billions of years ago, when this ocean partially froze, the ice expanded, breaking and stretching the ground above it. This process — referred to as cryovolcanism, or ice volcanism — is not at all like the rock volcanism that we see here on Earth or Io. But it forms the same kind of geologic features: valleys, ridges and resurfaced regions.

This finding broadened the way scientists were imagining volcanic eruptions. Volcanism is about more than just hot lava and explosive eruptions. Frozen water and ice can behave like molten rock on cold worlds, flowing, erupting and reshaping surface. In other words, many more worlds across the universe may be geologically active than was previously thought.

Callisto: The Moon That Failed to Change

Callisto has remained relatively heavily cratered with little sign of these other processes. Its surface is littered with craters — so many that there is little room left for new collisions to create additional, fresh craters. This ancient terrain is some four billion years old, dating back to the very birth of our solar system.

At first glance, Callisto might appear as the least intriguing of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons. But to planetary geographers, Callisto is precious exactly because it stayed the same. It’s like a time capsule of what was in the formative solar system.

Why Didn’t Callisto Evolve?

Callisto is also the farthest of the Galilean moons from Jupiter, and thus tides caused by the planet are much smaller. Without this energy input, its interior never got hot enough to power the geologic processes that made over its siblings. Callisto helps us see what happens when a world is born but doesn’t have the energy to continue evolving.

This tells us something vital about planetary geography: Change comes only with energy. Whether it is derived from internal heat, tidal forces or another mechanism, if a world lacks this energy it faces an eternity of stasis. This can help explain why some planets and moons in our own solar system are active, like Earth, while others are essentially dead.

The comparison between Callisto and its neighbors also shows how the location of a moon matters hugely. If Callisto were in Io’s orbit, it would look much more different. If Io orbited where Callisto did, its volcanoes would have ceased to flow at least a billion years ago.

Breaking the “Habitable Zone” Concept

For decades, there had been general agreement among astronomers seeking life beyond Earth that the “habitable zone” around a star — a region where a planet’s surface could support liquid water and perhaps life as we know it — was a narrow band at just the right distance from the star. Too close to the star, and water cooks off. Too far, and everything freezes. Earth just happens to nestle into the Sun’s habitable zone, which is why we have oceans and life.

It was the moons of Jupiter that demonstrated how narrow this concept is. Jupiter circles far beyond the bounds of habitable space, where temperatures drop to hundreds of degrees below zero. But Europa and Ganymede probably contain liquid water oceans, while the internal heat of Io is hot enough to melt rock.

The New Definition of Habitability

Today, when scientists talk about habitability, it’s in a different sense. As opposed to, “Is this planet in the habitable zone?” they ask questions like:

- Is there liquid water in any form anywhere on this world, even below the surface?

- Is there a source of energy that could support life?

- Is the scene right for organic chemistry?

- Can materials seep into one layer of the world from another?

By these new criteria, potentially habitable worlds span the solar system. The ocean seafloors of these two moons probably come into contact with the rocky centers of their oceans—and where water and rock meet, there’s a lot that can go on in those interactions to make it an environment like deep sea hydrothermal vents that are known to have teemed with life here on Earth.

This broader perspective on habitability also alters how we look for life in other solar systems. We now know that moons around giant planets orbiting in far-off regions of star systems might be places to look for life more than we should expect around their closer orbiting planets.

Jupiter’s Moons in Numbers

| Moon | Diameter | Distance from Jupiter | Orbital Period | Notable Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Io | 2,263 miles (3,642 km) | 262,000 miles (421,600 km) | 1.77 days | Most volcanic activity in solar system |

| Europa | 1,940 miles (3,122 km) | 417,000 miles (671,000 km) | 3.55 days | Subsurface ocean with more water than Earth |

| Ganymede | 3,273 miles (5,268 km) | 665,000 miles (1,070,000 km) | 7.15 days | Largest moon in solar system; has its own magnetic field |

| Callisto | 2,995 miles (4,821 km) | 1,170,000 miles (1,883,000 km) | 16.69 days | Most heavily cratered object in solar system |

How Modern Tech Reveals the Secrets of the Moons

Recent spacecraft and instruments have significantly advanced our knowledge of Jupiter’s moons. We saw our first close-up looks by way of the Voyager probes in 1979. This was followed by the Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter between 1995 and 2003 and examined the moons in levels of detail never before seen. The Juno probe orbiting Jupiter is still finding new things about the gas giant and its moons.

NASA’s future Europa Clipper mission, expected to reach Jupiter in 2030, will fly by Europa dozens of times at close range, using ice-penetrating radar to study the ocean below the surface. JUICE (JUpiter ICy moons Explorer), a mission of the European Space Agency, is going to take a closer look at Ganymede, Callisto and Europa to search for their habitability.

These missions use technology that didn’t exist when previous theories on planetary geography were formulated. We can now detect ice with radar. Spectrometers can pinpoint certain chemicals on faraway surfaces. Magnetometers pick up magnetic fields, and what they may divulge about the interior. Every step forward in technology causes scientists to go back and revise their theories.

The Ripple Effect on Planetary Science

The lessons from Jupiter’s moons have shaped how scientists study the planets and moons everywhere — not just in our solar system but around other stars as well.

Impact on Solar System Studies

When it was found that Saturn’s moon Enceladus had geysers spouting water ice into space, the whole thing only made sense once scientists grasped Europa’s subsurface ocean. Scientists were able to predict Pluto’s nitrogen glaciers and potential subsurface ocean in part because of what we learned from Jupiter’s moons. Now even Mars is getting a re-think —scientists have raised the possibility that ancient tidal heating might explain some of its early geological activity.

Impact on Exoplanet Research

Astronomers have found thousands of planets circling other stars, and countless of these worlds are thought to have moons. The fact that moons can be so geologically active, and potentially habitable, has led us to rethink how we assess these distant planetary systems. A giant planet orbiting far away from its star could have moons that are habitable, even if the planet could not be.

Now scientists are finally working out how to find exomoons (moons that orbit planets around other stars) and which ones might have the attributes that make Jupiter’s moons so intriguing.

Challenges to Old Theories

The findings at Jupiter have contradicted some long-held theories of planetary science:

The Size-Activity Connection: Researchers used to think that only big worlds could stay geologically active for billions of years. Smaller bodies like Earth’s Moon then cooled down rapidly and died. But Io, about the size of our own moon, is actually the most geologically active body in the solar system. It’s less a question of size than how much energy is being crammed into a space.

The Surface-Equals-Everything Hypothesis: Pre-Europa, scientists obsessed over surface features when examining planetary geography. We now know that subsurface oceans, invisible from the outside, can power surface systems and even life.

The Uniform Formation Theory: Initial theories proposed objects developing in the same area will be homogeneous. The striking contrasts among Jupiter’s four chief moons had demonstrated the power of local conditions — particularly gravitational interactions — to mold vastly different destinies for sibling worlds.

The Static Solar System View: Researchers used to imagine this solar system as untroubled for billions of years. Thanks to the moons of Jupiter we learned that stellar forces — tidal heating and orbital resonances — can shape worlds even in middle age, 4.5 billion years after the solar system first began to coalesce from lumps of dust and rock.

Implications for Future Exploration

The cognitive shift that has been catalyzed by the moons of Jupiter is a practical matter for space exploration. Knowing that small, frigid worlds can be geologically active and maybe even habitable alters mission priorities and budget allocations.

In the decades since, NASA and other space agencies have made going to icy moons a priority. Search for life now includes Europa, Enceladus and Titan in addition to Mars. Submarines might be sent to explore subsurface oceans, or perhaps drills that’ll penetrate ice shells kilometers thick.

The technical challenges are daunting, but the potential rewards are historic. If we find life in Europa’s ocean, or indications that the geysers of Enceladus originate from an environment that could support life, we would have to accept that places with conditions so extreme and strange can be inhabited. It would imply that life may be common throughout the universe, flourishing in hidden oceans around myriad icy moons.

The Ongoing Story

New findings keep on coming in about the moons of Jupiter. New research is indicating that Europa’s ocean could be much more Earth-like, support similar kinds of chemical conditions…and at times harbor those same kind of extreme life forms. There are hints in the data that Ganymede’s magnetic field may be interacting with Jupiter’s, and scientists hope to use this interaction to learn more about its internal ocean. Even minuscule moons orbiting well away from Jupiter are under study, as their bizarre orbits provide tales of the early solar system’s turbulent past.

Every piece is one more in the puzzle. And those processes are even more complex, varied and surprising than anyone could have imagined four centuries ago when Galileo first saw those four wandering lights around Jupiter.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many moons does Jupiter have?

Jupiter has at least 95 confirmed moons, and the tally keeps getting higher as astronomers discover smaller and more distant objects. The four Galilean moons are also by far the largest and most interesting for science.

Is there life on Europa?

Scientists think Europa’s ocean may contain the building blocks of life: liquid water, chemicals that could become “building blocks” for life and energy sources. Whether life exists on the moon remains yet to be discovered, but it is one of the most promising places in our solar system to hunt for alien life.

Why is Io so volcanic?

Io’s extreme volcanism is the result of tidal heating. Jupiter’s powerful gravity, together with the gravitational pull caused by the other Galilean moons, constantly flexes Io’s interior, causing enough heat to keep rock melted across the moon.

What is the depth of Europa’s ice shell?

Recent findings suggest that the ice shell of Europa varies in thickness, but it is generally thought to range from 10 to 15 miles thick. The ice could be relatively thin in some regions, which might allow future missions easier access to the ocean below.

Is it possible to see the moons of Jupiter from Earth?

Yes! You can see the four Galilean moons with binoculars or a small telescope. You can see them move around from night to night as they orbit Jupiter, just as Galileo observed over 400 years ago.

How long would it take to reach Jupiter’s moons?

Currently it takes space probes five or six years to get to Jupiter after launch. How long it takes to make that journey depends on the specific path they take, and specifically how Earth and Jupiter align along their orbits.

To Come: A Time for Discovery

The exploration of the moons of Jupiter is a real success story in planetary science. Starting with Galileo’s own first observations and extending all the way to modern, cutting-edge space missions, scientists have found something new and surprising in every generation. These findings have not only contributed to our understanding but have also completely altered how we think about planetary geography, habitability and the possibility of life beyond Earth.

The moons of Jupiter turned from simple points of light in a telescope into their own complex worlds with personalities, histories and secrets. They showed us that the universe is more diverse, more dynamic and more potentially habitable than we had ever imagined. The minuscule dots that helped to demonstrate four centuries ago that Earth is not the center of the universe continue to teach us, rewriting our understanding of how planets and moons form, evolve and might even support life.

As we get ready to launch new missions to study these captivating worlds up close, one thing is certain: Jupiter’s moons aren’t done astounding us yet. The next great discovery could literally be right around the corner, once again upending our understanding of planetary geography.