If you gaze up at the Moon on a clear night, you will see that the surface has dark spots and light patches spread across its surface. Those darker spots? Many of them are in fact giant craters that were formed billions of years ago. And yet, here on Earth, we have the Grand Canyon—a colossal scratch in the earth that runs for 277 miles. Craters and canyons are not enough though, they both tell only part of the story, sometimes amazing stories about how planets change and evolve.

And these geological features are more than just cool to look at. They are essentially history books written in rock and dirt, telling us what happened millions or even billions of years ago. From asteroid impacts that unleashed more energy than thousands of nuclear bombs to rivers that cut through solid rock over millions of years, the forces behind craters and canyons are among the most potent in forming our solar system.

In this article, we’ll look at how these fantastic features are created, why they vary in appearance from one planet to another and what scientists can learn by studying them. Whether you are interested in space or just like learning more about our own planet, knowing craters and canyons is a way to peer into the violent history — as well as the beautiful past — of worlds other than our own.

How Craters Explode Out of Nothingness

A crater forms when an object from space — like an asteroid, comet or meteorite — crashes into a planet’s (or moon’s) surface at very high speed. These strikes are more common than you might imagine, but most objects burn up in Earth’s atmosphere before they reach the surface.

The Impact Process

When a rock from space smashes into the surface of a planet, several things transpire within a few seconds:

Impact & Compression: The object impacts at velocities from 40,000 – 260,000 km per hour. At those speeds, both the impactor and surface compress in a manner analogous to squeezing together a spring.

Shock Wave Propagation: The impact develops into two shock waves propagating inside both the projectile and in the target. In the process, huge amounts of energy is released — enough to vaporize rock and melt whatever lies near.

Excavation: The shock waves drive material out and up, forming a cavity in the shape of a bowl. This thrown-out material is strewn over the surrounding area and deposited around the rim of the crater to create a raised rim.

Correction: Gravity tugs some of the material ejected back down. In bigger impacts the crater floor may even spring back up, so it has a central peak in the middle of the crater.

Energy Release

The energy of the impact is just mind-bending. A modestly sized asteroid only 1 kilometer across smacking into Earth would unleash the equivalent of around 47,000 megatons of TNT. That is more than a million times the power of the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima.

A Variety of Craters Across the Solar System

Craters aren’t all of a piece. They’re classified by scientists according to size and features.

Simple Craters

These are small, shallow or bowl-shaped depressions with smooth walls and a raised rim. Simple craters on Earth are generally under 2.5 miles in diameter. Meteor Crater in Arizona, for example, is about 0.75 miles wide and some 560 feet deep. It was created some 50,000 years ago when an iron meteorite crashed into the desert.

Complex Craters

When it’s a little bit bigger, that makes complex craters with terraced walls and flat floors, sometimes also a central peak or ring of peaks in the middle. This is because the force of impact is so strong that for a moment, the ground acts almost as if it were liquid. The inner walls slump downwards to form terraces while the floor rebounds upwards to become the central peak.

The Moon’s Tycho crater is a stunning example of a complex crater. It’s some 53 miles across, with a central peak that stands out and bright rays of ejected material that run for hundreds of miles along the lunar surface.

Multi-Ring Basins

The grandest impacts form multi-ring basins—massive features with two or more circles of mountains. They take so much energy that they only develop from the largest asteroids or comets. Valhalla is a huge crater measuring over 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers) in diameter that covers nearly the entire surface of Jupiter’s moon Callisto.

| Crater Type | Size Range | Notable Features | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | Up to 2.5 miles (Earth) | Bowl-shaped with smooth walls | Meteor Crater, Arizona |

| Complex | 2.5–60+ miles | Central peaks with terraced walls | Tycho (Moon) |

| Multi-Ring Basin | 60–1000+ miles | Multiple mountain rings | Valhalla (Callisto) |

Why Craters Can Look So Different on Other Planets

If you compare the craters on the Moon, Mars and Earth, they all look different because they were caused by impacts of similar-size objects and have developed over a range of environmental conditions. Numerous conditions determine how a crater is formed and what it looks like through time.

Atmospheric Protection

On Earth, we have a dense atmosphere; it’s our protective shield. Small space rocks burn up completely before they can hit the ground, producing meteors or “shooting stars” that light up the night. Only bigger things get through to form craters.

The Moon is virtually devoid of an atmosphere, and even small meteorites arrive at its surface. This is why the Moon is pockmarked with craters of all sizes, from giant basins to chasms smaller than your fingernail.

Mars has an atmosphere, albeit a thin one that provides some shade but little of the protection from impacts that Earth’s atmosphere gives. That is, Mars is struck by medium-size meteorites that would burn up in Earth’s sky but travel through Mars’ thin air with ease.

Gravity’s Role

A planet’s gravity also influences how material is ejected during an impact. On the moon, where gravity is one-sixth that of Earth’s, ejected material flies further before crashing back to the ground. This forms craters with broader ejecta blankets (the perimeter of debris).

On Jupiter or Saturn, the intense gravity would drag ejected material back down in no time, but then these gas giants have no craters in the first place — since they don’t have a solid surface.

Surface Composition

There also matters what a planet is made of. Smack a solid rock surface, and you make one kind of crater. Impact ice, and the product may be different. On Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus, some craters display evidence for “viscous relaxation”: Over time, ice slowly flows in such a way that old craters seem shallower and rounder.

Geological Activity

Earth is a geologically active world, with plate tectonics, erosion and volcanism all wearing down and building up the surface. This covers up most craters on time scales of millions of years. Researchers believe that Earth has been struck by thousands of big asteroids over the billions of years since it formed, but today there are only about 190 confirmed impact craters.

The Moon, on the other hand, is geologically inert. Craters that were born billions of years ago have hardly eroded or deformed, leaving a record of the tumultuous early history of the solar system in nearly pristine condition.

How Canyons Can Cut Their Way Through Planets

Canyons take millions of years to form, although craters can be created in moments. Craters are formed by getting the snot smacked out of them. These valleys and gorges are not.

Water Erosion: The Patient Sculptor

On Earth, most canyons are created when rivers slice through rock over huge amounts of time. The Grand Canyon is the most well-known example. For about 5 million to 6 million years the Colorado River has been cutting through layers of rock, but some of those at the bottom of the canyon are nearly 2 billion years old.

Here’s how water erosion works:

Hydraulic Action: The rock is eroded by the power of the water which traps air in the cracks and widens them as it crashes against the rock.

Abrasion: Sand and pebbles carried by the rivers rub against the rock like sandpaper.

Solution: Water dissolves some minerals in rock, particularly if the water is somewhat acidic.

The process is incredibly slow. It takes the Colorado River one thousand years to cut 6 inches from the floor of the Grand Canyon. But little by little, over millions of years, those minuscule adjustments stack up to a canyon that’s entirely more than a mile deep.

The Shifting Earth: Ripping the Ground Apart

At times canyons just happen because the ground simply splits apart. This occurs along rift zones, where tectonic plates are pulling away from one another. Great Rift Valley in East Africa is happening this way, as the African continent gradually splits into two parts.

These rift valleys can be massive. The Great Rift Valley system is over 3,700 miles long and extends from Syria to Mozambique. In a few million years, eastern Africa might break apart entirely to form a new ocean.

-

Ever wondered how continents move? 🌍 Read more: How Plate Tectonics Shape Our Continents Over Time

Wind Erosion: Desert Carvers

Wind can also cut canyons in dry environments, but they tend not to be quite as deep as those carved by water. Wind carries particles of sand and hurls them against the surface of rock, gradually eroding it. This process, known as deflation, can result in stunning slot canyons — such as those found throughout the American Southwest.

Antelope Canyon in Arizona is one such magnificent example. This narrow canyon has smooth, rounded walls that lack the rough edges of glacial carving; flash floods and wind erosion are believed to have been working together on the plateau for thousands of years.

Alien Canyons: Valleys on Other Worlds

Canyons are not the exclusive domain of Earth. Some of the most stunning canyons in the solar system are found on other worlds, and they were eroded by a variety of processes that we may or may not fully understand.

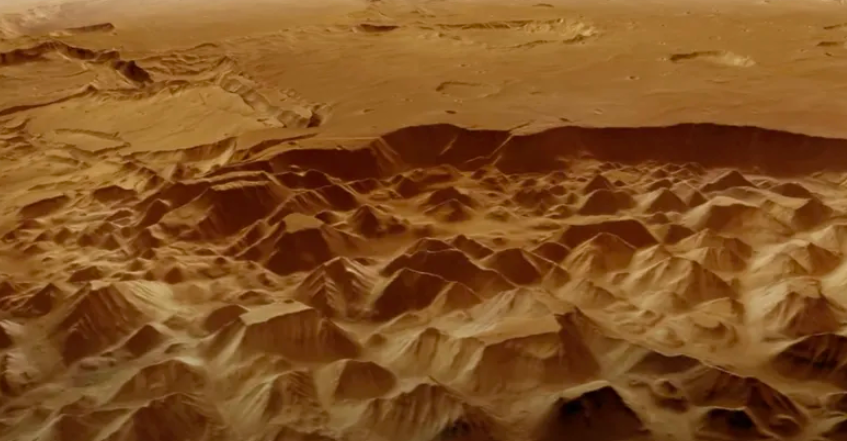

Valles Marineris: Mars’ Grand Canyon on Steroids

Valles Marineris is the largest canyon system in the solar system, located on Mars. This massive canyon surpasses the planet’s Grand Canyon in literally every aspect.

Let’s compare the two:

| Feature | Grand Canyon (Earth) | Valles Marineris (Mars) |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 277 miles | 2,500 miles |

| Width | Up to 18 miles | Up to 370 miles |

| Depth | 6,093 feet (1.1 mile) | More than 23,000 feet (4.3 miles) |

| Formation | Water erosion | Tectonic rifting |

Laid out on Earth’s surface, if you plonked Valles Marineris down here it would go from Los Angeles to New York City. It is believed the canyon began to form when volcanic action in nearby Tharsis caused the crust of Mars to stretch, with the Martian equivalent of rift valleys on Earth emerging.

Though water didn’t form Valles Marineris, there is evidence that water once flowed through it and eroded and widened some segments. Rivers that ran in the ancient past could have fed into the canyon system, forming temporary lakes billions of years ago during Mars’s time with a thicker atmosphere and warmer temperatures.

Titan’s Methane-Carved Valleys

Only one other object in our solar system has stable liquids on the surface: Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. But instead of water, Titan has lakes and rivers of liquid methane and ethane.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft observed river valleys on Titan that appear strikingly similar to river valleys here on Earth. These valleys formed as liquid methane eroded out channels in Titan’s icy surface – drainage networks that pour into methane seas.

The fact that Titan’s valleys bear a resemblance to Earth’s canyons, carved by water, is evidence of the same physical processes being put to work no matter which liquid is doing the carving.

Europa’s Chaotic Terrain

Jupiter’s moon Europa has a smooth icy shell overlying a hidden ocean. Some areas of Europa’s surface display “chaotic terrain”—jumbled spots where the ice has cracked up, moved around and refrozen. Some of these areas have canyons where the ice is broken and drifting apart.

These ice canyons were created in ways that differed from rock canyons. Jupiter’s gravitational pull pulls on Europa, stretching it out and cracking its icy surface. Some scientists believe that warm water below occasionally penetrates through and melts and shifts the ice above.

What Planetary Surfaces Reveal About Their History

To scientists, craters and canyons are like a page in a history book. By examining these features, scientists can reverse-engineer what happened on a planet millions or billions of years ago.

Dating Surfaces

One of the most valuable aspects of craters is that they help scientists deduce just how old a planetary surface might be. The logic is straightforward: the more craters a surface has, the older it likely is. This is called crater counting.

If scientists can count craters on a particular surface, they can guess when it formed. Here’s why this works:

There used to be a lot more asteroids and comets flying about shortly after the solar system formed. Impacts were much more common.

The vast majority of these objects over time either collided with planets or were ejected from the solar system.

Today, impacts are far less frequent than they were 4 billion years ago.

By calculating the number of craters in different places and comparing one portion against another, researchers are able to create a relative timetable. The Moon’s heavily cratered highlands, for example, are far older than the smoother maria (the dark areas you see), which resulted from lava flows that buried earlier craters.

Climate History

Canyons reveal climate history. On Mars, networks of valley networks (branching patterns that resemble dried up river systems) inform us that water used to traverse the Martian surface. This suggests that its atmosphere must have been considerably thicker, and the temperature on Mars warmer—even more dissimilar to how it is today as a frigid desert.

The layers of rock that are revealed in canyon walls also contain records of climatic conditions. The successive layers were deposited under different conditions, and scientists can read them the way they do tree rings to learn what ancient climates were like.

Geological Processes

The way craters look can disclose what lies beneath a planet’s surface. When an impact punches its way through layers of rock, it exposes those layers like cutting into a layered cake. Geologists use exposed layers like these to study a planet’s geological history without drilling deep holes.

Canyons reveal even more layers, providing scientists cross-sections of planetary crusts. The rock layers of the Grand Canyon reveal almost 2 billion years of Earth’s history. Each layer is part of the story: ancient seas that once flooded the region, volcanic eruptions, changing climates and the jostling of mountain ranges.

Time and the Appearance of Planetary Surfaces

Crater formation and erosion processes interact to determine the appearance of planetary surfaces today. It’s sort of a battle between destruction (by impacts) and construction (erosion, tectonic activity and volcanism).

Preservation vs. Erasure

Craters vanish pretty fast on geologically active worlds like Earth. Plate tectonics recycle the crust, erosion obliterates crater rims, and vegetation blankets impact sites. The crater, known as the Chicxulub impact, is in Mexico and is a barely visible remnant today. It was an event 66 million years ago that contributed to killing off the dinosaurs.

On dead worlds such as the Moon or Mercury, craters last for billions of years. Countless craters, soon erased by erosion and found only in continents like North America, Australia and Africa that are shielded from an ever-shrinking Moon, were already less than 4 billion years old. The result is a surface pocked with craters, each of which new impacts can strike only by removing material from old ones.

The Fresh vs. Degraded Spectrum

Craters are sorted by scientists in categories based on how eroded or “degraded” they appear.

Fresh craters have distinct rims, are bright (with clear ejecta blankets), and have sharp features.

Some of the degraded craters have lumpy rims, floors filled in or less well defined features due to erosion and being buried by other impacts.

By examining how worn a crater is, scientists can guess how old it is and how actively erosion processes are working in an area.

Exploring Craters and Canyons: How Scientists Learn About These Features

Today, though, with the help of new technology, researchers are able to investigate craters and canyons in unprecedented detail — even on faraway worlds that they may never visit.

Orbital Imaging

Spacecraft that orbit planets and moons send back high-resolution images of surfaces below. These images show off the craters and canyons in gorgeous clarity. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, for instance, has snapped images of the moon in resolutions high enough to see boulders the size of cars.

Not all cameras show the same things:

Visible light cameras depict what the surface would look like to human eyes.

Infrared cameras sense heat and can tell one rock type from another.

Radar absorbs dust and is capable of showing what lies beneath.

Laser Altimetry

Laser altimeters, which bounce laser beams off the ground and measure the time it takes for them to return, directly measure the precise height of surface features. This results in ultra-accurate 3D maps of craters and canyons, displaying their depth, volume, and shape in meter-resolution accuracy.

Rover Exploration

For planets we can reach by rovers — right now that’s only the Moon and Mars — these remote explorers can drive right up to any craters, or over any canyons they see and study them up close. On Mars, the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers have driven across ancient dried-up lakebeds and deep canyons, examining rocks and seeking evidence of past life.

Rovers come equipped with very sophisticated equipment capable of:

- Taking microscopic photographs of rocks

- Using lasers to analyze rocks in order to determine the rock’s chemical makeup

- Drilling samples from rocks

- Examining the minerals in various rock strata

Computer Modeling

Impact scenarios and erosion processes are simulated by powerful computers. Such models aid researchers in learning about how craters form, how ejecta is distributed and how landforms change over time.

By adjusting variables in those simulations — for example, impact speed, the size of the impactor or gravity — scientists can test hypotheses and predict what they should find on other worlds.

Notable Craters and Canyons to Remember

Let’s visit some of the most fascinating and significant craters and canyons in the solar system.

Vredefort Crater, South Africa – Earth’s largest verified impact structure (though it has been significantly eroded). Created some 2 billion years ago by an asteroid some six miles in diameter, the original crater was approximately 185 miles wide. Yet today we are left with a partial ring structure that enables us to study the impacts of extremely old events.

Copernicus Crater, Moon – A beautiful complex crater spanning approximately 58 miles in diameter, visible with prominent terraced walls and central peak cluster. It’s relatively youthful (roughly 800 million years old), so it still looks fresh with bright rays that stretch more than 500 miles.

Gale Crater, Mars – Present site of NASA’s Curiosity on the red planet since 2012. Mount Sharp is a mountain of layered sedimentary rock at the crater’s center and measures 96 miles wide. For years, Curiosity has been climbing all over these hillsides of Mount Sharp, decoding how the environment shifted as each layer came to be.

Hellas Planitia, Mars – The largest visible impact crater in the solar system; at 1,400 miles across, it’s seven times wider than Grand Canyon but only about an eighth as deep. The collision that formed it had to be catastrophic, flinging material either entirely off Mars and into space.

Hverfjall Crater, Iceland – This is not actually an impact crater but a volcanic one created from violent explosions around 2,500 years ago. And it’s a wonderful demonstration that not all craters come from space — volcanic activity can also cause features like you see here.

Fish River Canyon, Namibia – The largest canyon in Africa and the second largest in the world (only the Grand Canyon in the U.S.A is bigger). One hundred miles long and up to 1,800 feet deep, it was created through the combination of water erosion and tectonics over the course of millions of years.

Future Directions in Crater and Canyon Research

We continue to learn more about craters and canyons as our technology gets better, as we explore the solar system more.

Sample Return Missions

The most exciting thing happening in planetary science are sample return missions — spacecraft that fetch rocks and bring them to Earth to be closely studied. NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission brought back asteroid Bennu samples, and Japan’s Hayabusa2 mission did the same with asteroid Ryugu.

Missions in the future may also be able to drill at craters on Mars or the Moon, bringing scientists impact materials that can be studied with laboratory precision that is not possible using rover instruments alone.

Human Exploration

NASA’s Artemis program expects that it can return humans to the moon in a few years. Astronauts will explore around the lunar south pole, where there are many ancient craters that are never sunlit. Inside these permanently shadowed craters is water ice, just waiting to be harvested as a potentially precious resource for future lunar bases.

Someday, human explorers on Mars may explore Valles Marineris up close—rappelling down its walls to examine rock layers laid bare and covered with dust in the search for ancient life.

New Technologies

Artificial intelligence, and specifically machine learning, are changing how scientists identify and catalogue craters. Rather than manually sift through thousands of images, AI can automatically spot and quantify craters, greatly accelerating research.

Advanced radar systems could soon scan the subsurface of icy moons such as Europa and Enceladus, which might contain canyons and other features in their subsurface oceans.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can scientists tell the difference between an impact crater and a volcanic one?

Typical impact craters possess raised rims, ejecta blankets, and in some cases central peaks or peak rings. Volcanic craters form at the tops of volcanoes and have different shapes (i.e. they aren’t usually bowl-shaped with raised rims or ejecta). The rock around impact craters also displays shock features from the high pressures of slamming into something, which volcanic rocks lack.

Can an asteroid cause a canyon on Earth?

Not directly. Impacts form bowls, not long lines of them. But impacts can also help to indirectly form canyons by causing weaknesses in rock that water later takes advantage of, or by altering drainage patterns across a region. However, the canyon carving itself involves some erosion processes that occur on much longer timescales.

Why isn’t Earth as heavily cratered as the Moon?

The Earth has probably been struck by about as many asteroids as the Moon, but Earth’s active geology wipes out most signs of impacts. Plate tectonics recycle the crust, and it could be eroded by terrestrial water, wind or ice – vegetation might also obscure its impact site. The Moon is barren of both an atmosphere and water, and has no plate tectonics to erase the marks a crater leaves behind; craters remain in pristine condition for billions of years.

Which is the solar system’s deepest canyon?

That distinction goes to Valles Marineris on Mars; some parts of that system are about 4.3 miles deep — much deeper than Earth’s Grand Canyon. When it comes to underwater canyons, however, Earth’s Mariana Trench is deeper at approximately 7 miles — although it’s technically an ocean trench created by plate tectonics and not a canyon.

Can new craters still form on Earth today?

Yes! Meteorites strike Earth often, but most are small and burn up in the atmosphere. About once a year, a car-size asteroid enters Earth’s atmosphere and gets burned up as a spectacular fireball. Every few decades, perhaps a small meteorite would form a crater just a few meters wide. Far larger impacts that can create much larger craters occur far less often — typically every few thousand to million years, depending on the size.

How do researchers determine the age of craters?

For terrestrial craters, researchers rely on radiometric dating of impact-melted rocks or shocked minerals. For other planets, they rely on crater-counting statistics: the number and size of craters compared with surfaces of known age. For a subset of the returned Apollo lunar samples, absolute ages determined by radiometric dating provide calibration points for crater counting on other airless bodies.

Where on earth can you observe craters forming?

Chances are you’re not going to see an impact crater forming — the big ones occur so infrequently that no human has ever observed one being made. But you can go check out fresh impact sites. The most serious recent impact occurred in Chelyabinsk, Russia, in 2013, when a meteoroid exploded high above the ground, sending out a shock wave that shattered windows and damaged buildings. Tiny pieces of the meteorite fell to earth, forming small impact pits in the snow and ice.

Could the Grand Canyon form on Mars?

Theoretically, yes, if Mars had liquid water for long enough then it could have cut these valleys. Mars’ atmosphere is too thin today to keep water in liquid form on the surface and it’s far colder than Earth. The river valleys and canyons that we observe today on Mars were carved billions of years ago when the planet was warmer and wetter. New water-carved canyons cannot form under present conditions on Mars, but the landscape is still slowly being sculpted by wind erosion.

The Timeless Tale Carved in Rock and Ice

Craters and canyons aren’t just neat surface features of worlds around the solar system — they’re records of cosmic violence, slow erosion and the very processes that carve and craft planets over billions of years. Each crater recounts the final seconds of an asteroid in cosmic free fall, explosions that vaporized rock and remolded terrain. Every canyon exposes the never-tiring toil of rivers, wind, tectonic forces or (in one case at least) alien liquids cutting through solid ground.

And those features link us to the larger tale of our solar system. It turns out that the processes that produced the craters we see on the moon billions of years ago are still going on there today. It’s the same physics that allow water to gouge the Grand Canyon at work on Titan, which has methane rain that cuts valleys into ice. By examining craters and canyons, we don’t just learn about other worlds, but also our own planet’s role in a dynamic — sometimes violent but always fascinating — cosmic neighborhood.

And as we continue to scan our solar system with improved technology, and one day human explorers, there will be new craters and canyons that upend our understanding of the universe and shed light on how planets are born, change, endure or cease. Every discovery is another page in the continuing story of our solar system — a tale written in stone and ice, marked with craters from impacts long ago that we are just beginning to read.